The Expanding Role of Intracardiac Echocardiography in Electrophysiology

Interview With Jason Chinitz, MD

Interview With Jason Chinitz, MD

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2026;26(2):Online Only.

Interview by Jodie Elrod

In this interview, Jason Chinitz, MD, from South Shore University Hospital within Northwell Health, discusses the central role of intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) in advancing procedural safety, efficiency, and operator control—spanning fluoroless atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation, left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO), and concomitant procedures. He details his experience integrating Philips ICE technologies, the clinical and workflow challenges they help solve, and why he believes ICE is becoming an essential skill for electrophysiologists as procedural volumes rise and imaging expectations continue to grow.

Tell us about your EP practice and what makes your lab unique.

I work at South Shore University Hospital, an academic tertiary care center within Northwell Health, the largest health system in New York. Our electrophysiology (EP) lab serves as a regional referral center and is closely integrated with several community hospitals in the Northwell network, allowing us to receive and treat patients requiring more complex procedures. As a result, we have developed a high-volume program with significant expertise in ablation—particularly AF ablation—as well as LAAO procedures.

I work at South Shore University Hospital, an academic tertiary care center within Northwell Health, the largest health system in New York. Our electrophysiology (EP) lab serves as a regional referral center and is closely integrated with several community hospitals in the Northwell network, allowing us to receive and treat patients requiring more complex procedures. As a result, we have developed a high-volume program with significant expertise in ablation—particularly AF ablation—as well as LAAO procedures.

We currently have 2 dedicated EP labs and are in the process of adding a third within the next year. Our team includes 3 full-time EP faculty and an additional 3 electrophysiologists from our network who perform procedures in our labs. We are fortunate to work alongside a highly experienced group of EP nurses, technologists, and skilled physician assistants. Looking ahead, we will welcome our first cardiology fellowship class in 2026, and we are excited to continue expanding our role as a teaching hospital.

When did you start utilizing ICE technology and why did you start incorporating it?

ICE has long been a cornerstone of our approach to AF ablation and ventricular tachycardia ablation. Like most electrophysiologists, we rely on ICE as a critical tool—not only for understanding cardiac anatomy but also for monitoring complications, assessing catheter positioning, and evaluating catheter contact. It has been integral to our workflow for many years.

These skills positioned us well to become early adopters of fluoroless ablation. Moving away from fluoroscopy forces you to refine your imaging abilities and rely more heavily on ICE, which ultimately provides far greater anatomical detail than fluoroscopy ever could. When we began performing LAAO procedures, we initially used transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), but gradually incorporated ICE into these cases as well. At first, this was out of necessity—patients with esophageal varices or other esophageal abnormalities, or those who could not tolerate general anesthesia, made TEE challenging. In these situations, ICE provided a viable alternative.

As we gained more experience, we began to appreciate the broader advantages of using 3D ICE for LAAO. We recognized potential safety benefits by avoiding TEE, reducing need for general anesthesia and intubation, and we found improvements in procedural efficiency, scheduling flexibility, and independence from requiring additional imaging specialists during the case. Personally, I found that guiding LAAO with 3D ICE gave me greater control over the procedure. It reinforced that electrophysiologists can manage the imaging component themselves—just as we do in other EP interventions—and it deepened my understanding of anatomical relationships. This independence made the procedure even more enjoyable, and I came to see imaging as a fun part of the case.

I believe 3D ICE can reduce overall procedure risk and offers potential cost savings over TEE imaging for LAAO. It naturally evolved into our primary imaging modality for LAAO. This was even more evident as we began performing concomitant AF ablation and LAAO procedures. Since we were already using ICE for ablation, it made sense to use one 3D ICE catheter to support both the ablation as well as the LAAO portion of the procedure.

What challenges did Philips ICE solutions help you overcome? How has using Philips ICE solutions impacted your patient care and outcomes?

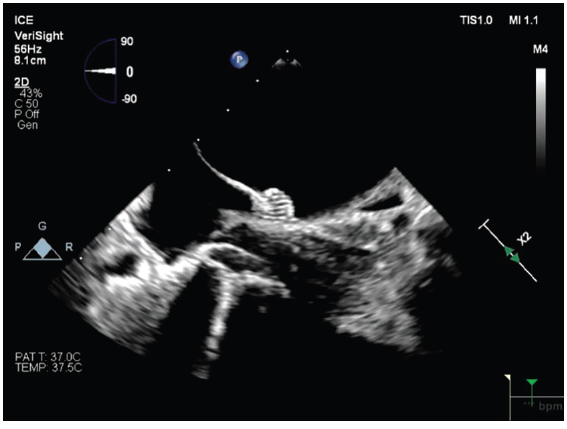

We began using the VeriSight Pro 3D ICE Catheter (Philips) to support our LAAO procedures. Incorporating 3D ICE streamlined the workflow and enhanced procedural safety, but what stood out most was the clarity of the imaging. The high-definition views provided by the VeriSight Pro allowed me to visualize the LAA, the occlusion device, and surrounding anatomical structures with exceptional detail.

There are several additional advantages to this catheter. Because we are using these catheters in the LA, there was concern about whether manipulation of the ICE catheter in the LA could increase risk of perforation; however, the VeriSight Pro’s atraumatic tip offers an added margin of safety, reducing the risk of perforation even with necessary manipulation. Its 3D technology enables multiplanar imaging with minimal catheter movement, allowing us to obtain multiple essential views while keeping the catheter largely in a single position. This significantly simplifies performing LAAO with 3D ICE. The ability to generate 3D reconstructions and use 3D color Doppler flow further enhances our understanding of anatomical relationships and helps confirm the absence of peri-device leaks.

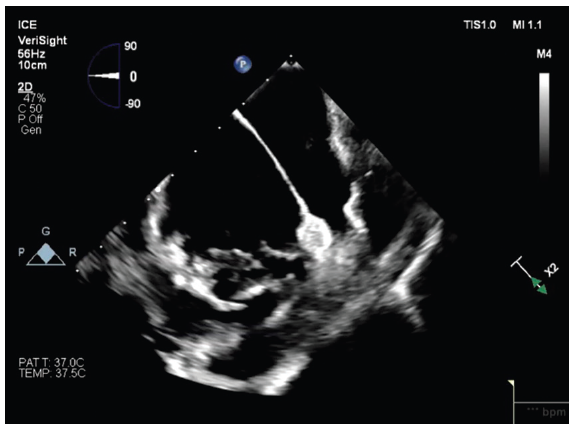

I also gained experience with the VeriSight Single Plane Steerable ICE Catheter (Philips) and found it similarly valuable—particularly because of its markedly improved 2D image resolution and quality, which is especially helpful for guiding ablation.

What drives your decision to use 2D vs 3D ICE?

Ultimately, my choice of catheter is driven by the specific needs of the procedure we are performing. In my lab, the VeriSight Pro 3D ICE Catheter has been particularly useful to support LAAO procedures. The ability to obtain multiple viewing angles, digitally rotate images, and achieve multiplanar visualization with minimal catheter movement has simplified my ability to obtain multiple imaging views to guide LAAO, and has become my standard approach for these procedures.

In contrast, for ablation procedures without structural interventions, 2D ICE catheters remain our standard.

In the majority of our ablations, we are also relying on electroanatomical mapping systems that provide 3D reconstruction and minimize the additional need for 3D imaging.

I have found the VeriSight Single Plane Steerable ICE Catheter to deliver consistent high-resolution 2D imaging, and to be easy to maneuver both in the right and left atria during ablation procedures.

What advantages does VeriSight Single Plane Steerable ICE Catheter provide in AF ablations?

The 2D image quality is excellent, and the atraumatic tip allows it to be maneuvered safely throughout the heart during AF ablations. The digital steering is a promising feature as it enables us to track catheter position with less manual manipulation. Steering can be adjusted at the EPIQ CVx Ultrasound System (Philips) or via a foot pedal, which has the potential to enhance imaging efficiency and free the operator’s hands to focus on the ablation.

I find this catheter especially useful when supporting pulsed field ablation (PFA) for AF because it provides visualization of catheter position and tissue contact in a way that is difficult to achieve with mapping systems alone. Because PFA catheters do not offer the same contact force feedback we are accustomed to with modern radiofrequency ablation catheters, we rely on other indicators of contact. In my view, high-resolution ICE is the most reliable way to confirm catheter–tissue contact and assess the consistency of that contact throughout the ablation.

I have also found significant benefit in placing the VeriSight Single Plane Steerable ICE Catheter into the LA via transseptal access. This approach provides remarkable views of the pulmonary veins (PVs), particularly the right-sided veins, which can be challenging to visualize from the right atrium (RA). The perspective from within the LA gives us a much clearer understanding of catheter positioning, ensuring adequate contact and confirming that we are delivering lesions precisely where we intend around the PV antra.

You mentioned the importance of seeing anatomical relationships. Can you help me understand a bit more about how that impacts you as a physician, and how ICE enhances your ability to appreciate those anatomical relationships in ways other imaging modalities may not?

Having clear imaging is essential for accurately understanding catheter position. Catheter contact is critical—you can only be confident that you have consistent contact if you can directly visualize the catheter remaining on the tissue throughout the ablation. But understanding the anatomical relationships is equally important. We know we need to target the PVs, particularly the antral aspects, yet these areas can be challenging to visualize when imaging is limited, especially from the RA.

By steering the ICE catheter into the LA, we gain a clearer appreciation of PV anatomy and orientation relative to the LA, and how our catheters lay in relation to the PV antra. Detailed ICE imaging from the LA allows us to see these relationships far better than before, ensuring that our ablation catheter is in contact with the intended areas and that we are truly treating the tissue we aim to ablate.

This is especially important for lesion durability. Consistent contact is essential for long-lasting lesions. With PFA, we can be fooled into thinking that we are making good ablation lesions because everything initially appears well ablated. However, without good catheter contact, these lesions will not be durable.

From your perspective, ICE really allows you to confirm ablation contact and ensure that the lesion set is shaped and completed exactly as intended. Would you say that ICE gives you a clearer ability to assess this compared with alternatives such as TEE or relying solely on the mapping system?

With high-quality ICE imaging, we can directly visualize the catheter within the PVs and confirm that it is making circumferential contact with the tissue. That level of detail is not attainable with the mapping system by itself.

When we use TEE for LAAO, we rely on specific imaging angles—standard probe positions that are helpful for the imager but, as the proceduralist, do not truly convey how we are viewing the LAA. With ICE, you move away from thinking in terms of angles and instead focus on anatomical relationships. For example, you ensure that structures such as the aortic valve or mitral valve are in view when imaging the LAA, which gives you a more clear sense of orientation and how you are imaging the LAA. Thinking about imaging in this manner provides a deeper understanding of LA and LAA anatomy than can be obtained by imaging based on standardized TEE angles.

You mentioned the additional control that VeriSight provides, particularly in terms of steerability and some of the capabilities within EPIQ CVx. Can you elaborate on how it offers more control and how this impacts you as a physician during procedures?

There are really 2 aspects of control. The first relates to the catheter itself. It is relatively easy to manipulate both in anterior and posterior and left and right directions, which is essential when we need to manipulate the catheter in the LA. Its ability to steer effectively and respond predictably to fine movements allows the control we need to guide the catheter into and within the LA.

The second aspect of control comes from using ICE as the imaging modality to support LAAO procedures rather than TEE. By eliminating the need for a separate imaging cardiologist, the operator performing ICE-guided LAAO now has control of all aspects of the procedure, and is no longer reliant on another physician’s availability and scheduling limitations. Furthermore, the potential safety concerns associated with TEE imaging are eliminated.

Tell us about your learning curve with ICE, including adoption. Can you tell me more about that journey and how you adapted to using ICE in these procedures?

As electrophysiologists, we already have a significant advantage when it comes to adopting ICE. Most of us have extensive experience with 2D ICE for supporting ablation, so adopting these skills to support LAAO procedures is not entirely new territory. Over time, becoming more comfortable with 2D and 3D ICE has become an essential skill in our field. It has enabled us to perform fluoroless procedures as well as LAAO and concomitant procedures independently. In my experience, the learning curve is fairly rapid when you already have that foundation. You can accelerate the process by intentionally reducing your reliance on TEE and fluoroscopy. When we transitioned to fluoroless procedures and shifted imaging responsibility entirely to ourselves, it forced us to become more skilled with ICE imaging.

Another factor that significantly enhanced my comfort with ICE was using it to evaluate the LAA for thrombus before ablation. Traditionally, we relied exclusively on TEE for this. But over the past few years, we have learned that ICE is often a feasible alternative. It does require placing the ICE catheter in various positions to adequately visualize the LAA, but once we developed those skills, our comfort with ICE imaging of the LAA improved considerably.

So, in my opinion, the learning curve for electrophysiologists is not particularly difficult. It simply requires the desire to do it.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Concomitant procedures offer a unique opportunity to use 3D ICE catheters to support AF ablation. It can be difficult to justify using a 3D ICE catheter to support ablation alone because lower cost 2D alternatives are typically sufficient. However, when we are already planning to use a 3D ICE catheter for LAAO, we can take advantage of the 3D catheter to image during the ablation. This allows us to appreciate added benefits such as multiplanar imaging and 3D reconstruction and how they can supplement imaging during ablation—capabilities we otherwise would not have access to during ablation with 2D ICE imaging. Concomitant procedures also encourage electrophysiologists to adopt and become more comfortable with ICE-guided LAAO and placing the ICE catheter transseptally into the LA.

More broadly, I see ICE as a key aspect to procedural control and a critical skill for electrophysiologists. As the procedural environment becomes more cost conscious and the volume of AF ablation and LAAO continues to grow, it will become increasingly difficult to rely on an imaging cardiologist for every case—particularly given the opportunity cost of their time. For these reasons, I expect ICE-guided procedures to become the standard in the future.

I also believe the technology is evolving rapidly. The image quality we once considered adequate is now obsolete, and expectations for ICE performance have increased dramatically. The EPIQ CVx Ultrasound System is currently one of the highest-quality imaging platforms we have. But this is only the beginning. I anticipate that we will soon leverage ICE not just for visualization, but for deeper insights into tissue characteristics. Imaging will guide decisions about where to ablate and how much to ablate based on tissue thickness and characteristics. In time, artificial intelligence may play a role as well, with potential to provide automatic measurements and live feedback regarding imaging findings during our procedures.

The transcripts were edited for clarity and length.

Dr Jason Chinitz has been compensated by Philips for their services in preparing and presenting this material for Philips’ further use and distribution. The opinions and clinical experiences presented herein are specific to the featured physicians and the featured patients and are for information purposes only. The results from their experiences may not be predictive for all patients. Individual results may vary depending on a variety of patient-specific attributes and related factors. Nothing in this material is intended to provide specific medical advice or to take the place of written law or regulations.

Disclosures: Dr Chinitz has completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. For the present work, he reports consulting fees from Philips. Outside the present work, he reports participation on a medical advisory board and consulting fees for Johnson & Johnson MedTech, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic; and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events for Boston Scientific.

This content was published with support from Philips.