ADVERTISEMENT

Comparison of Nurse Practitioner and Physician Practice Models in Nursing Facilities

Nurse practitioners (NPs) are competent primary care providers in long-term care (LTC) facilities who provide an extensive range of services. The inclusion of NPs on the care team has been associated with fewer hospitalizations and emergency department transfers; improved health status, behavior, and satisfaction with care; and increased quality of care among LTC residents. Secondary data analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey for 2006 through 2010 was conducted to compare the practice patterns of NP and physician (MD) provider cohorts in order to evaluate whether the primary care practice model influences the process of care for LTC nursing facility residents. The sample consisted of data from Medicare beneficiaries who resided in a nursing facility for a full year, yielding 1322 measurements. NPs and MDs provide primary care for similar patients with regard to demographic variables, reported health status, and deficits in activities of daily living. NPs provide comparable care that is both substitutive and complementary to that provided by MDs in LTC. Health screening rates were similar, although NPs had higher completion rates of advance directives related to do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. The results of this study validate the key role of NPs in primary care for older adults. By having a higher completion rate of DNR orders, the inclusion of NPs in LTC nursing facility care teams potentially increases resident quality of life and reduces the cost of care by minimizing the use of costly, unwanted treatments.

Key words: Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), long-term care, secondary data analysis, nurse practitioner, advance care planning.

As the number and diversity of older adults in the United States increase, so does the demand on the healthcare service industry to provide quality long-term care (LTC) for this population. Among the strategic areas identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for improving the health and quality of life of older adults are appropriate health screening, preventive services, and the promotion of advance care planning and awareness of end-of-life issues.1

There were approximately 205,000 licensed nurse practitioners (NPs) in the United States in 2014; approximately 15% of these NPs have privileges in the LTC setting.2 For over 25 years, NPs have demonstrated that they are competent primary care providers in LTC facilities.3 For instance, the inclusion of NPs on the care team has been associated with fewer hospitalizations and emergency department transfers;4 improved health status, behavior, and satisfaction with care;5 and increased quality of care3 among LTC residents. NPs are educated to promote health and to identify common syndromes in older adults in collaboration with the resident, family, and healthcare team to ensure comprehensive healthcare for this population. Early studies have shown that NPs play substitutive and complementary roles to that of the physician (MD), and their diverse skills were instrumental in enabling policy decisions that encouraged full utilization of NPs.6-8 A 2004 national survey of NPs in LTC settings identified an extensive range of services that NPs provide at their facilities, with sick/urgent visits, preventive care, regulatory visits, hospice care, and wound care being among the most common.9 Further, NPs are regarded as being highly effective in both delivery of services and resident, physician, and family satisfaction.8,9

In a 2013 systematic review of the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses (APNs), which include clinical nurse specialists and NPs, Donald and associates5 reported that residents of LTC facilities with APNs experienced lower rates of depression, urinary incontinence, pressure ulcers, restraint use, and aggressive behaviors. In addition, these facilities had more residents who saw improvements in meeting their personal goals and more family members who expressed greater satisfaction with medical services provided to their loved ones. Further, Bourbonniere and associates10 identified NPs as having a positive impact on resident care and LTC facility outcomes in their 2009 article, which reported on recommendations from a 2003 expert panel. A 2008 literature review by Bakerjian11 supported NPs as “primary care providers to improve management of chronic care conditions, better manage functional status, spend more time in the facility, and make more average visits per month.” Additional benefits associated with NP care of nursing home residents were reduced costs to the healthcare system and facilities; reduced resident mortality; improved satisfaction of families, residents, staff, and physicians; and fewer emergency department visits and acute care hospitalizations.11

Quality of care and total costs have been shown to be similar for teams consisting of both NPs and MDs as well as MD-only models of care in LTC facilities. It has been reported, however, that residents cared for by NPs are seen more frequently, suggesting an increase in access to care and consultation.12,13

Much of what is known about NP practice in skilled nursing facilities is based on capitation programs employing NPs to care for LTC nursing facility residents. Although research demonstrates the effectiveness of NPs in improving resident health outcomes, most studies were conducted within a limited practice or geographic area and were not generalizable to all NPs. Further, samples for the intervention studies tended to be small.

In their 2015 study, Abdallah and colleagues14 assessed the variation in health status and functioning of nursing home residents receiving primary care services from NPs, MDs, and physician assistants (PAs). Secondary analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) from 2006 through 2008 revealed that functioning did not vary significantly by practice model; however, residents cared for only by MDs experienced significantly diminished orientation and independence in activities of daily living (ADL) compared with residents who received more than one-half of their primary care visits from an NP or PA.

The purpose of this research study is to investigate the differences in NP and MD practice patterns in LTC nursing facilities. It was hypothesized that the process of care would vary by type of primary care model. It was further hypothesized that the process of care variables would reflect the complementary nursing role of the NP, in addition to the medical substitutive role, and that this may account for any differences observed between the two practice models.

Methods

Data Source

This study protocol was approved by the University of Massachusetts Lowell and Framingham State University Institutional Review Boards. Primary care services provided to Medicare beneficiaries residing in LTC nursing facilities within the Medicare program were analyzed using data from the MCBS for the years 2006 through 2010 (in accordance with the United States Department of Health & Human Services, CMS data use agreement approval). The MCBS is a continuous, multipurpose survey of a nationally representative sample of the Medicare population, conducted by the Office of Enterprise Data and Analytics (OEDA) of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)15 through a contract with Westat (Rockville, MD). The main objectives of the MCBS are to ascertain the expenditures and sources of payment for all services used by Medicare beneficiaries and to track processes over time (eg, changes in health status, satisfaction with care, usual source of care).

For this investigation, we examined data from Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 years who resided in a nursing facility for the full year. Responses from the nursing facility sample were made by proxy using nursing facility staff three times per year for up to 3 years, and these data are linked to Medicare claims data. Data files were purchased from the CMS; all data development was performed by the CMS and were available as public use files.

Medicare regulations require that NPs practice with a collaborating or a supervising MD in the LTC setting. We therefore evaluated and compared two primary care models: MD only practices and MD/NP collaborative practices. Using Medicare claims data included with the MCBS cost and use data, study subjects in each year were categorized into either of two following cohorts: (1) MD only (ie, patients receiving all primary care visits from a physician) and (2) NP involved (ie, patients receiving one or more primary care visits from a NP during the year reported).

The sample yielded 1322 subject observations from 2006 through 2010: 858 (64%) in the MD-only cohort and 464 (36%) in the NP-involved cohort. Nearly 40% of study subjects died during each year.

Analysis

The MCBS uses a stratified, multistage area probability sample design. Due to the complex nature of the sample design, weighted procedures were used that accounted for this complexity. Survey weights, clusters, and stratum are provided for subjects in each year. Thus, to ensure that our multiyear data were still representative of the Medicare population, survey weights were averaged and then adjusted for the number of years that a subject is followed (dividing the survey weights by the number of years that each subject is represented in the data).16 Two statisticians extracted relevant data into smaller files for use and analysis by the team. Observations with missing data for each comparison were excluded from that comparison; for each analysis, patients with missing data were excluded. For this reason, the sample sizes differ for many comparisons.

Differences were tested for significance at the level of P<.05 using the Rao-Scott chi-square test, a design-adjusted version of the Pearson’s chi-square test. The age differences were tested using a weighted regression procedure with Taylor series approximations for the standard errors of the regression estimates. SAS 9.3 software was used in all analyses.

Results

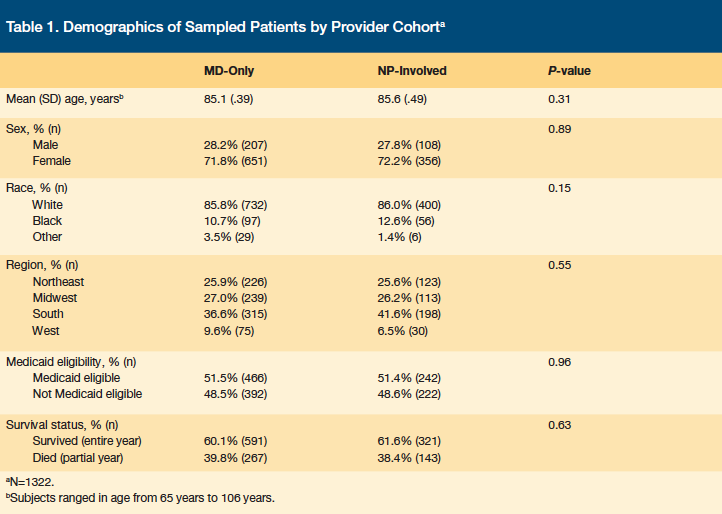

There were no differences found between practice models with regard to gender, race/ethnicity, or age of residents cared for. Subjects were predominately white women between 65 and 106 years of age (Table 1). The residents in the MD-only cohort were more likely to reside in nonmetropolitan-area nursing homes, whereas residents in the NP-involved cohort were more likely to reside in metropolitan-area nursing homes (P=.009).

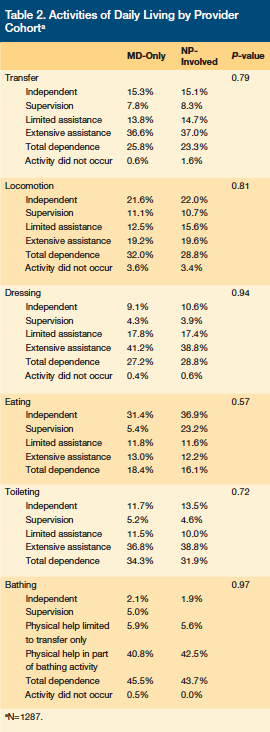

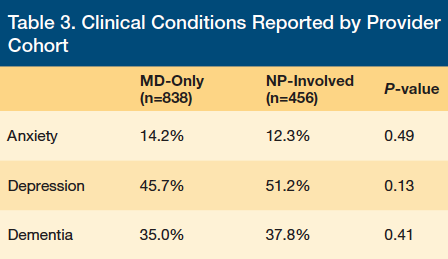

Reported health status did not differ by practice model (P=.16). Residents cared for by NPs and MDs were reported to have similar deficits in ADL performance (Table 2). The MD-only and NP-involved cohorts also had similar rates of residents with a diagnosis of anxiety, depression, and/or dementia (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences between primary care models on measures of dental/oral health, bowel and bladder continence, reported vision and visual appliance use, or reported hearing or hearing aid use.

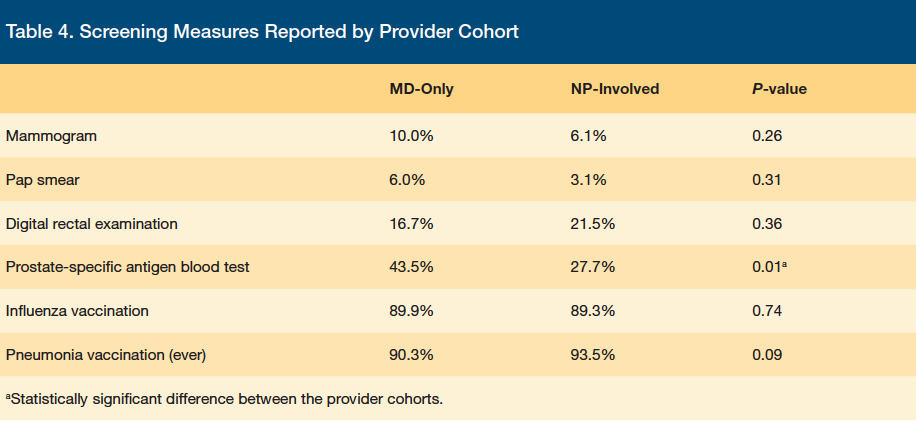

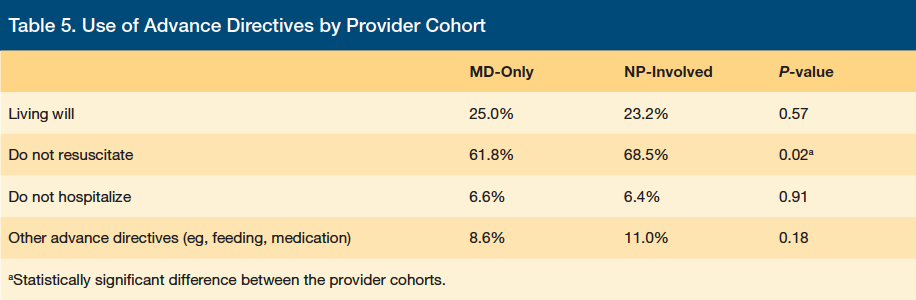

Similar rates of influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations, mammograms, Pap smears, and digital rectal examinations were recorded for both the MD-only and NP-involved cohorts. However, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood tests were ordered with greater frequency in the MD-only group (P=.01; Table 4). For advance directives overall, there were no differences among provider cohorts for living wills, Do-Not-Hospitalize orders, or advance directives related to feeding, medication, or other restrictions. However, the NP-involved cohort had significantly more DNR orders than the MD-only cohort (P=.02; Table 5).

Discussion

Results of this analysis indicate that there were no differences in the process of care provided within the two primary care practice models. Both MDs and NPs provide primary care for similar patients with regard to demographic variables, reported health status, and deficits in ADL. It has previously been reported that 96% of institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries have difficulties with one or more ADLs, and 83% have difficulty with three or more ADLs.17 There were also no differences detected for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). IADL are those that nursing home residents would not likely be involved in by virtue of their nursing home eligibility (ie, preparing meals, shopping, managing money, using the telephone, doing housework, and taking medication).17

In the area of health screenings, there were few differences detected between the two practice models. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) identifies a need for specific screening recommendations for adults aged ≥65 years, in part because of the higher prevalence of disease and higher disease burden among these patients. Yet, there is little information in the literature that addresses the relative value of preventive services to older adults in the presence of cognitive impairment and functional limitations.18 Additionally, the USPSTF recommends against Pap smear screening in women over the age of 65 years who are not at high risk and against the PSA blood test for prostate cancer screening.19 These recommendations reflect the uncertainty of the usefulness of screening in frail older adults. In our analysis, the PSA blood test screening was ordered with significantly greater frequency in the MD-only practices.

This study confirms results from a prior study that reported that NP-involved practices consistently had a significantly higher completion of advance directives than did the MD-only practice model.20 The NP-involved cohort had more DNR orders recorded. This could imply that NPs are more likely to initiate discussions regarding advance directives and end-of-life care with their residents in this setting. In the MCBS analysis, there were no differences noted in the presence of living wills among the provider cohorts.

A limitation of our study relates to its sample size. Although a national sample was evaluated, the amount of data available for specific comparisons of nursing facility residents by cohort model was relatively small for drawing conclusions regarding practice differences. Moreover, the MCBS includes only the few measures of preventive care included in this report. Additionally, the lack of clinical definitions in the data led to some ambiguity; for example, it was not evident from the coded data whether dementia and Alzheimer’s disease or cardiovascular disease and hypertension were mutually exclusive and may have resulted in duplication of data points. Furthermore, proxy responses by staff were obtained for the MCBS survey for 100% of the nursing facility population, without any indication of inter-rater reliability. A limitation of secondary data analysis is that the items examined were not developed specifically for this study and the data were obtained to answer a different research question. There is the potential that interviewer bias may have affected the data in the sample. This may have limited the analyses possible.

There is a growing shortage of primary care providers for older adults due to both retirement of practicing primary care providers and a decline in students choosing primary care careers.21 The increasing life expectancy of Americans with accompanying chronic diseases further compounds this shortage.22 Few physicians choose to specialize in geriatrics due to the additional training required to achieve certification and the disproportionately low pay.21

The Institute of Medicine has recognized the ability of NPs to provide primary health care, recommending that they should practice to the full extent of their education and training and that they be full partners with physicians and others in the shaping of healthcare.23 Half of all NPs currently work in primary care;24 conversely, the supply of specialist physicians far exceeds the number of primary care physicians,25 highlighting the growing role of NPs in filling the gap in the provision of primary care.

Educational programs for NPs regarding the care of older adults have increased in number, in response to the need for gerontological primary care providers. The adult and gerontological curricula have been merged, leading to the preparation of NPs with the competencies required for both populations.26 With fewer health care providers certified or specializing in geriatrics in the United States,27 including gerontological content in NP educational programs offers an important option to meet the primary care needs of nursing facility residents.

Conclusion

NPs have provided high-quality services to LTC residents for many years.3 The results of this study validate the key role of NPs in health promotion and treatment and suggest NPs take a greater initiative to assess the advance care planning preferences of residents in the LTC nursing setting, potentially reducing the initiation of costly, unwanted treatments. The study supports previous research showing that NPs provide comparable care that is both substitutive and complementary to that provided by MDs in LTC. The current shortage of primary care physicians is likely to increase with the enactment of the Affordable Care Act. Policy implications of this trend should include national standardization of licensing requirements and the removal of restrictions to independent NP practice and reimbursement. For example, Medicare regulations that require all skilled nursing facility patients be admitted by physicians, and that alternating regulatory visits must be with physicians,28 may need to be revisited. Utilization of the NP to the full extent of their preparation will help to ensure an adequate supply of primary care providers for LTC residents in the future.

1. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy Aging: Improving and Extending Quality of Life Among Older Americans: At a Glance 2009:1-4. CDC website. www.cdc.gov. Published 2009. Accessed November 3, 2015.

2. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP Fact Sheet. www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet. Published 2002. Accessed November 3, 2015.

3. American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Legislation/Regulation Fact sheet: Long Term Care. AANP Website. www.aanp.org/legislation-regulation/68-articles/351-fact-sheet-long-term-care. Published March 2012. Accessed November 3, 2015.

4. Christian R, Baker K. Effectiveness of nurse practitioners in nursing homes: a systematic review. JBI Library of Systematic Reviews. 2009;7(30):1333-1352.

5. Donald F, Martin-Misener R, Carter N. A systematic review of the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses in long-term care. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(10):2148-2161.

6. Melillo KD. Nurse practitioners in long-term care: Perceptions of DONs. Journal of Long Term Care Administration. 1992;20(3):13-17.

7. Melillo KD. Utilizing nurse practitioners to provide healthcare for elderly patients in Massachusetts nursing homes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 1993;5(1):19-26.

8. Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White KM, et al. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990-2008: a systematic review. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(5):230-250.

9. Rosenfeld P, Kobayashi M, Barber P, Mezey M. Utilization of nurse practitioners in long-term care: findings and implications of a national survey. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(1):9-15.

10. Bourbonniere M, Mezey M, Mitty EL, et al. Expanding the knowledge base of resident and facility outcomes of care delivered by advanced practice nurses in long-term care: expert panel recommendations. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2009;10(1):64-70.

11. Bakerjian D. Care of nursing home residents by advanced practice nurses. A review of the literature. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2008;1(3):177-185.

12. Aigner MJ, Drew S, Phipps J. A comparative study of nursing home resident outcomes between care provided by nurse practitioners/physicians versus physicians only. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(1):16-23.

13. DesRoches CM, Gaudet J, Perloff J, Donelan K, Iezzoni LI, Buerhaus P. Using Medicare data to assess nurse practitioner-provided care. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61(6):400-407.

14. Abdallah LM, Van Etten D, Lee AJ, et al. A Medicare current beneficiary survey-based investigation of alternative primary care models in nursing homes: functional ability and health status outcomes. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2015;8(2):85-93.

15. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) website. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/index.html. Updated September 1, 2015. Accessed November 3, 2015.

16. Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Doubeni CA, Chen Y, Rao SR. Methodological issues in using multiple years of the Medicare current beneficiary survey. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012,8(1):E1-E19.

17. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Community Living. Disability and Activity Limitations. Administration on Aging (AoA) Website. www.acl.gov. Published 2014. Accessed November 3, 2015.

18. Butler M, Talley KMC, Burns R, et al. Values Of Older Adults Related to Primary and Secondary Prevention: Evidence Syntheses, No. 84. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); March 2011.

19. US Preventative Task Force. The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014.

20. Lawrence JF. The advance directive prevalence in long-term care: a comparison of relationships between a nurse practitioner model and a traditional healthcare model. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(3):179-185.

21. Center for Workforce Studies: Association of American Medical Colleges. Recent Studies and Reports on Physician Shortages in the US. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Website. http://report.nih.gov/investigators_and_trainees/acd_bwf/pdf/recentworkforcestudiesnov09.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed November 4, 2015.

22. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, Hauer KE. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(8):774-749.

23. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Published October 2010. Accessed November 3, 2015.

24. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Highlights from the 2012 National Sample Survey of Nurse Practitioners. HRSA Website. Published 2014. Accessed November 3, 2015.

25. Hing E, Hsiao CJ. State Variability in Supply of Office-Based Primary Care Providers: United States, 2012. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Data Brief Number 151. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db151.htm. Published May 2014. Accessed November 3, 2015.

26. Stanley JM. Impact of new regulatory standards on advanced practice registered nursing: the APRN Consensus Model and LACE. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(2):241-250.

27. American Geriatric Society. The Demand for Geriatric Care and the Evident Shortage of Geriatrics Healthcare Providers. American Geriatric Society Website. www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/Adv_Resources/demand_for_geriatric_care.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed November 3, 2015.

28. Bakerjian D, Harrington C. Factors associated with the use of advanced practice nurses/physician assistants in a fee-for-service nursing home practice: a comparison with primary care physicians. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2012;5(3):163-173.